Arthur Szyk, Israel, detail. Fairfield University Museum. Photographed by Samuel Abelow.

On a warm October day, I left my family home in Connecticut, driving up a reclusive road. Vibrant midday light illuminated the leaves' holy array of yellows, oranges and dark browns, like a stained glass window.

Typical for me, my head up in the trees, I pushed down on the brake and came to a full stop. There was a red fox in the middle of the road.

I once wrote about how red foxes are a symbol in ancient alchemy as well as in Guaguin’s artwork for instinctual desire. The powerful appearance of the animal evokes aspects of psyche – archetypes. The red is like fire, fire is hot; human’s get heated and do animalistic things. (May Heaven help us.)

On October 7th, about two weeks before this excursion described above, Hamas infamously attacked civilians in Southern Israel. The terrorists performed barbaric acts.

Jewish people read the Torah throughout the year in sections. The reading of that very week was the story of the Flood in the times of Noah. It was noted by many, including my rabbi, that Hamas is mentioned in in the Flood episode.

“The earth became corrupt before God; the earth was filled with lawlessness.” - Genesis 6:11

The word used in the Torah for lawlessness, which commentators describe as being connected to sexual immortality in the extreme, as well as robbery, is חָמָֽס (Hamas).

The mystic asks: Where is this Hamas in me? That is the red fox. My own inner animal, which when left untamed, can do the unspeakable.

This asking of oneself, “Where I my inner Hamas”, that is the mystical approach. This is the Jungian approach of “shadow work.” However, Arthur Szyk was an artist-activist, a polemic illustrator. Syzk looks outward, with ideaology.

I look inwards, to the mystical, with curiosity.

His solution is to be political. My solution is to connect to the ancestoral wisdom.

Arthur Szyk in New Yorker

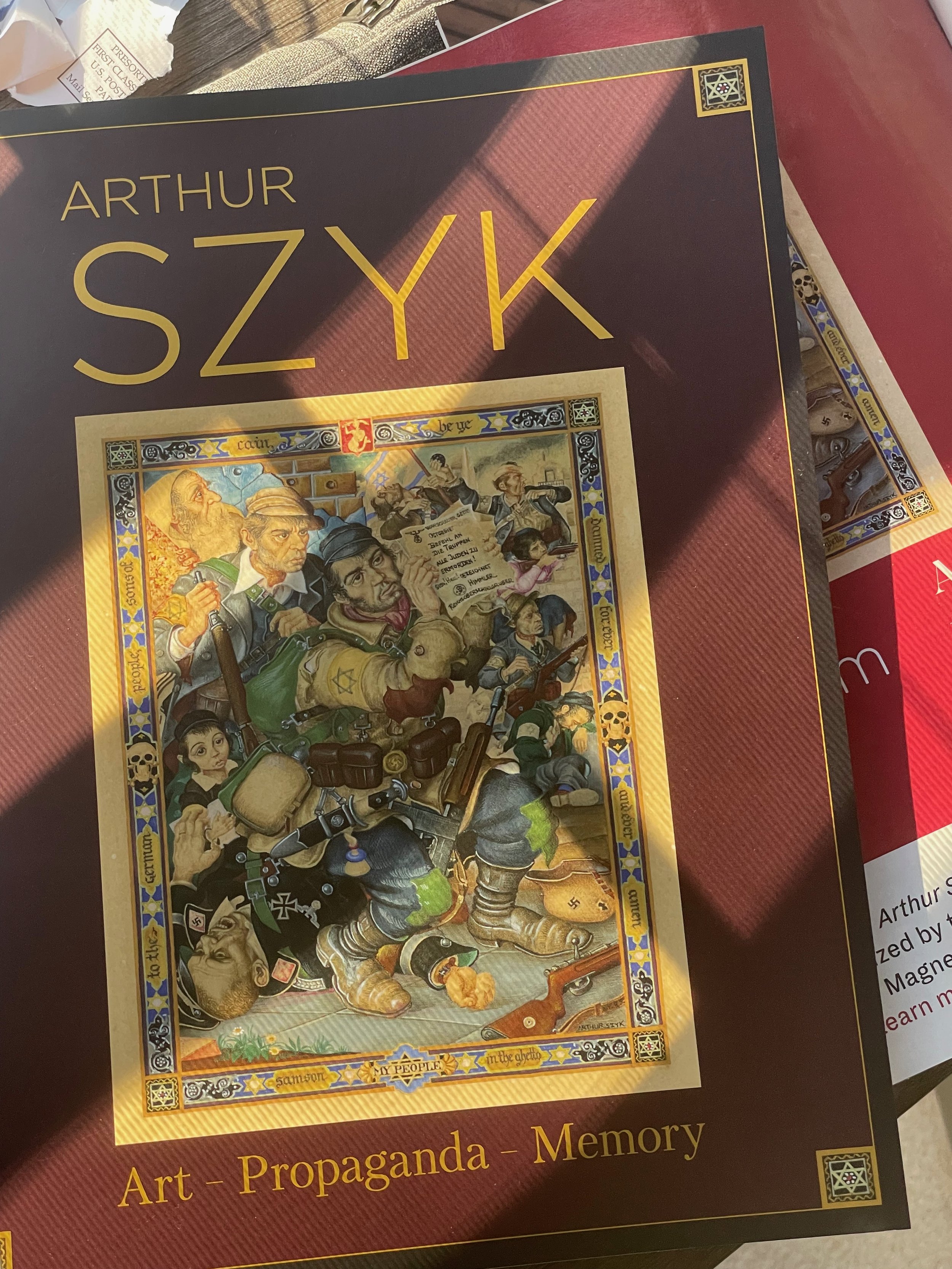

I traveled to the university museum on a Wednesday. That previous Saturday, as the Sabbath came to a close, my friend Levi Paris asleep upstairs, I flipped through the New Yorker – a magazine subscription my parents have had for decades. The very last page was an advertisement for an exhibition at the local university gallery:

In Real Times - Arthur Szyk: Artist and Soldier for Human Rights.

This, I recognized, was synchronicity, a term C.G. Jung coined for meaningful coincidences. This was hashgacha pratis (Divine Oversight, as the jewish mystics like to say). Two weeks ago the beginning of the war in Israel, and this exhibition is up, while I happen to be in Connecticut for a little break from Brooklyn.

The Jewish Problem

Jewish art isn’t really a thing. Jews are a people of the book. And modern artists who happen to be Jews – Modigliani, Picasso (Yes! On his mother’s side), and Rothko (formerly, Rothkowitz) – don’t really deal with their Jewishness in a direct way.

Arthur Szyk was an illustrator, cartoonist, and political activist, but his work, in a larger context, is the work of an artist. Reviewing his work, I saw how his multicultural sensibility and honoring of women as empowered individuals, precluded later movements: it is that pioneering, intuitive activity that makes an artist, an artist. [ see: https://www.samuelabelow.com/blog/vision-of-the-artist-in-society ]

My limited understanding of Szyk, informed by the exhibition, is that his life’s work represents a jew in exile, diaspora, who eventually reached what he saw as the safe haven and opportunity of America. Arthur Szyk honored historical figures who stood for the rights of all people.

The Canadian government commission illustrates Szyk’s belief in nationhood, celebration of diversity and hope in Israel.

Many of the works on display mock evil, albeit with keen use of detail, both in penmanship and in astute awareness of the events of his day.

But, what stood out to me most was the underlying spirituality and soulfulness to Arthur Szyk: a representation of Queen Esther in his original Megillah, a pendant for the Jerusalem Museum featuring a regal Jewish woman, I imagine to be the Matriarch Rachel; the artist hearkens towards the fundamental source of our individual creation, the woman; and the ultimate purpose of creation; to make the world a dwelling place for the divine.

I apologize if that got mystical. I tend to dream when I’m awake, and wake up when I dream.

Dr. Lipman

I might add that a collector of my work and a dear friend, mentor and fellow jew in exile, Dr. Lipman joined me for the gallery tour.

We discssued the current events. Dr. Lipman passionately spoke about Israel’s right to exist. I realized that the doctor is an extension of Szyk’s generation: acknowledging one’s Jewishness as an identity and focusing on the political issues. This ideaological approach, which might honor instituitions like America or Israel, is outward looking.

Meanwhile, myself, born several generations later, I’m influenced by developments in psychology and an intensification around spirituality: the remedy is not found in activism, but in mysticism, in connecting to something greater and taking responsibility for the depth of self; the deeper reality of being a Jew.

At the end of our time in the exhibit, the doctor turned to me and said: “Sam, you are a remarkable person. I don’t know where you’ll end up, but I’m certain it will be of significance.”

Dr. Lipman continued, “I’m not a religious man, but I do know that all the events of one’s life are designed by God. Your art, talents and mind are a part of this larger story of history. Stay the course.”

After writing this essay. Some time passed. There was a Sabbath the weekend of October 27th. A reported 7,000 people marched the streets of Brooklyn chanting “From the River to the Sea Palestine Will Be Free!” (a slogan which implies the annihilation of jews in Israel). This was a Sabbath where a team of cops protected the synagogue where I prayed and communed.

I sat down at the breakfast table on at my yeshiva Monday morning, preparing to finish this blog. Twenty young men were oddly silent. I said:

I said, in a orator tone, “I’ve been praying; been praying for a good day.”

And I continued, “There’s so many things I can’t explain. I let them hang. Why? That’s the play.”

Someone said, “Is this a poem?”

“I’ve been praying, praying for a good day.”