“Father and Child,” Ruby Sky Stiler, 2018. Picture via https://nicellebeauchene.com/exhibitions/fathers/

Thursday night, as I attempted to wind down to sleep, in the lower floor of my sister’s apartment in Brooklyn, my inner vision filled with the Archaic Greek geometries. Early that evening, I had attended Ruby Sky Stiler’s solo show, “Fathers” at the Nicelle Beauchene Gallery in New York City.

Stiler’s geometric designs had stayed with me; There were thousands of little square bits, each performing a swirl, zig-zag, or some other simple expression. These glyphs, I have seen before. They occurred in a particular psychedelic trip in one other basement living room — that of a high school friend. The basic human designs are both the access point, the entry door into the full-blown psychedelic vision, and the patterns which both the ancients favored and contemporary children tend to doodle.

Please click to enlarge images throughout the article

A Walk Back Through History

The potency of this experience may also have been evoked by a walk through the Greek and Roman galleries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art earlier that afternoon. Perusing the many ceramics, amulets and statues dating back 2,000 years, I was struck with a keen awareness of humankind’s instinctual and ongoing need to decorate, design, ornament surroundings and objects with the universal motifs of living and the geometries that please the eye. This essentially human need, nourishing to viewers, is what draws so many tourists to the Metropolitan each year.

“Siblings with Father, “ Ruby Sky Stiler, 2018. Picture via https://nicellebeauchene.com/exhibitions/fathers/

Ruby Sky Stiler’s use of decorative elements, simplified line and mosaic-like representation of anonymous figures is emblematic of this perennial tradition and appetite found throughout the history of civilization.

In Stiler’s work, these archaic influences are blended with the austerity of modern architecture, design, and sculpture. Also, academic Cubism, as well as Bauhaus theories of aesthetics are evident in Stiler’s geometric designs.

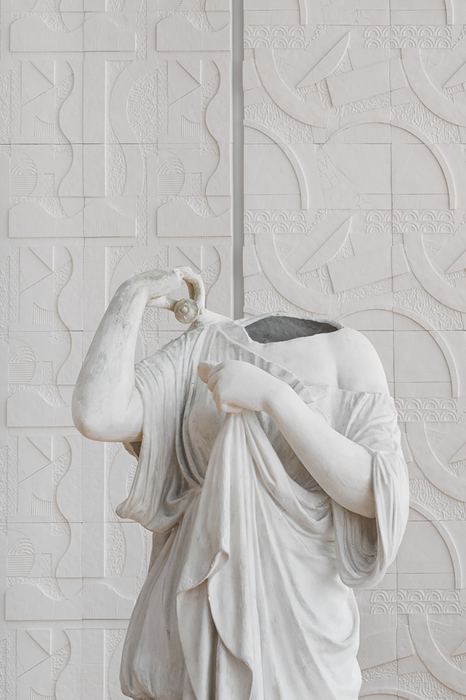

Installation view (detail), Ruby Sky Stiler, 2015. Photograph at the Aldrich Museum via http://rubyskystiler.com/projects/ghost-versions-the-aldrich-museum-ct-2015

In various interviews, the artist makes allusions to the way in which her work challenges notions of authenticity, authorship, ownership, as well as the relativity of value. This is because the decorative elements in her work often include quotations from ancient Greece. At the Aldrich Museum, in 2015, she paired her minimalist friezes with plaster copies of Greek and Roman statues. Stiler mentioned that this offered, “the opportunity for us to embrace ideas about anonymous authorship, copies and simulacra. The imitation of more elevated materials and the question of skill and craft, high and low.” [1]

In ancient cultures, such as the Assyrian and Egyptian empires, art was a state-run, religious affair. Up until the Renaissance, art featured very little individuality. It wasn’t until Michelangelo and Raphael that the artist as personality, an “Art Star,” was truly established. Since then, this has become the norm, as modernist artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat solidified the artist as synonymous with a recognizably individual brand, rather than with the identity of an artisan, or commissioned craftsperson.

It is fascinating to see a contemporary artist such as Stiler so explicitly delve back into the archaic roots of creative expression. The deeper into history one goes, the more evident the cross-pollination of style and form becomes, and the less authorship and cultural identity can be ascribed and ownership over an approach claimed.

Whether it is the Egyptian influence on the Minoans (c. 2000 BC), the Jewish influence on early Roman culture (c. 300 AD), the Arabic influence on the Renaissance (c. 1100 AD), or the Japanese influence on the Impressionists (c. 1890 AD); Or in reverse direction, the Roman influence on the Byzantine culture, which fed into the Islamic East (c. 500 AD), influencing styles of illustration and painting in modern day Iran and India; Or better yet, the example of Alexandria, where cross-pollination of Jewish, Islamic and early Christian sects occurred, along with combinations of Roman and Egyptian motifs and styles; Wherever one points, this cultural cross-assimilation is an integral part of human culture history. [2]

Certainly, it is apparent that, in the context of modern artistic conventions, Ruby Sky Stiler’s work questions authorship and cultural identity . However, in an increasingly secular culture, we are all tasked with curating, organizing our own aesthetic sensibilities and moral values. Stiler has an exceptional ability to re-configure imagery of the ancient past, early modernism, with the materials of now.

In a time where the imagery and ideas from all time are available at the click of a mouse, we can re-arrange and examine them according to our own proposed meaning; This may be the only meaning available to those who are no longer held by the container of the religions passed down through their own countrymen and family.

Ruby Sky Stiler’s artistic practice acknowledges the vitalizing effect of metabolizing diverse material. It is this reconfiguration of the past and present in her work which is so appealing.

The Modern (Female) Artist

Among Stiler’s modern interpretations of archaic ideas, I find the influence of ancient practices of mosaic particularly interesting.

“Lod Mosiac,” Roman (5th Century BC), Photograph by Niki Davidov/Israel Antiquities Authority. Picture via http://www.hadassahmagazine.org/2011/08/17/438/

The so-called “Lod Mosaic,” a massive arrangement produced by the Romans in Jerusalem (c. 200 AD) is a fantastic example of multicultural influences finding expression in a formalized, decorative art.

“Mosaic Floor with Views of Alexandria and Memphis” Gerasa (540 AD). Picture via https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/51363 ]

The “Mosaic map of Alexandria and Memphis” (540 AD) resides in the Yale Art Museum. It is likely that this specific object influenced Stiler since Yale is where she attended graduate school.

Ruby Sky Stiler’s reference to floor mosaics pushes her work deep into antiquity. This archaic residue provides a latent, or implicit nod to the “purposes” of such arts to the ancients themselves.

It is recognized by most scholars that ancient decorative and artistic work functioned as devotional, magical devices. [3]

Evidence of ancient human activity regarding ritual, magic and religious practice as a way of pleasing the gods, can now be understood psychologically as related to the projection of psychic energy onto the outer world and artistic objects. Still, it is empirically true that by making concrete our feelings and thoughts through writing, painting or design, we incarnate our will and actualize our values.

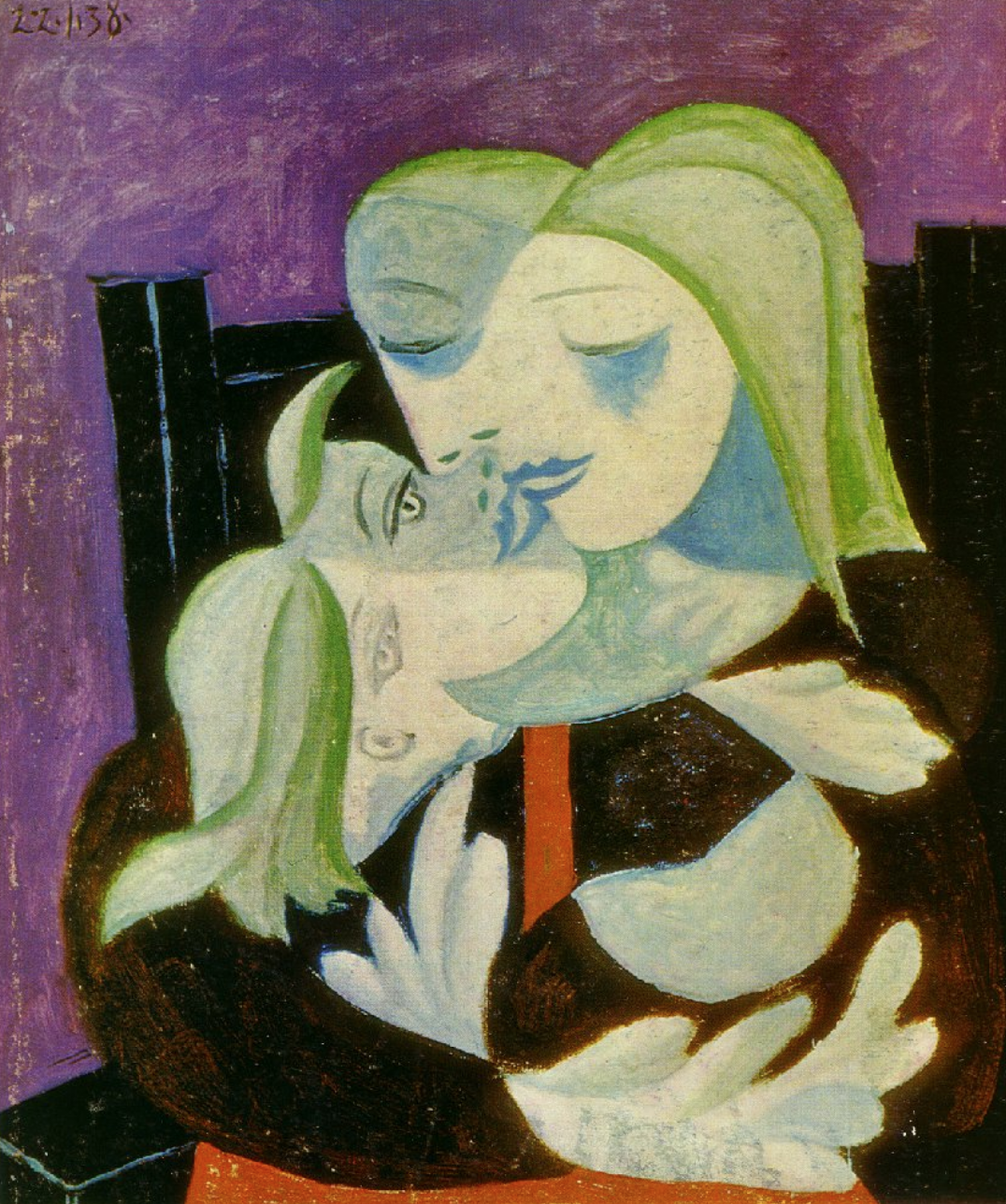

Stiler literally “draws out” — consciously brings into existence — her desire to reconfigure the maternal demands and expectations of womanhood. She asserts the artist as a female role and emphasizes the paternal aspect of man. She makes the father and son relationship and imago her muse, just as Picasso did with the mother and child.

Below are a selection of paintings of the “Mother” from throughout Pablo Picasso’s oeuvre

In the press release for the “Fathers” show, writer Lumi Tan suggest that Ruby Sky Stiler’s work puts the father and son as a reaction against the Madonna and the effect such archetypal images continue to have on social mores surrounding motherhood and acceptable social identities for women. [4]

The abundance of imagery produced by male artists representing the mother and child is challenged by Stiler in the latest show. The two central paintings in the front room feature the father and son motif, while the two central paintings in the back room feature the woman with a vessel. This dichotomy is also mirrored in her two figurative wood sculptures; one represents the father and son unit, the second, placed separately is the woman.

Following along with the interpretation suggested by Tan, the identity of the artist as a woman is key. The paintings displayed in the back room become representations of the aspect of women as artist (rather than historically the muse or Madonna), distinct from the maternal.

This split, between the front and back room of the gallery emphasizes the ascendence of the artist’s devotion to creative expression and aesthetics (the vessel). The dynamic between the two rooms in this show may well contain the notion that the woman-artist is an increasingly codified identity, and that the paternal man is her counterpart (at least in this case). I would also suspect that sometimes — with a specific sort of modern consciousness — this role may reverse and be shared mutually amongst the sexes; this may be true for Stiler herself, as her husband, Daniel Gordon, is also a working artist.

Author of “Goddesses in Everywoman,” Jean Shinoda Bolen writes about the various aspects of a given female psyche. Relevant to Stiler’s work, we can examine the “Aphrodite” type and the “Demeter” or “Hera” type; the first being the creative, expressive, artistically devoted and the latter two having maternal, family-oriented characteristics. Bolen’s chapter on the creative aspects of the “Aphrodite type” describes, “creativity as a ‘sensual’ process; an in-the-moment sensory experience involving touch and imagery. An artist engrossed in a creative process, like a lover, often finds that all her senses are heightened and that she receives perceptual impressions through many channels.” [5]

I can, within reason, identify Stiler in this typology based on an interview which appeared in Bomb Magazine. Speaking of her artistic practice, Stiler revealed: “I discovered that my brain is not as smart as my hands are. My intelligence comes through the process of making the object and that’s where I have the potential to learn something and create something unexpected. I don’t really even make sketches anymore. It’s futile for me because I can’t imagine how the thing should be before I work on it.” [6]

Bolen explains on an intrapsychic level, what Tan addresses as a cultural issue: “Aphrodite often threatens the priorities of the Hera and Demeter archetypes — monogamy or the maternal role — so the latter often have judgmental attitudes toward Aphrodite.” [7]

As long as the artist is conscious of such inner pulls, and can hold the tension and acts in a way to keep the dynamic in balance, this seeming conflict is ultimately resolved, and provides a rich, fulfilling and complex life.

Amplification of Ruby’s “Fathers” Imagery

As much as this external, cultural interpretation is compelling, we may further continue to explore Stiler’s work with an intrapsychic lens — viewing the imagery as reflective of aspects of her own personality. In this way, there is a difference nuance: We see a woman’s interest, fascination with the father-son relationship she is witnessing in her personal life evoking an intensity of feeling to particular archetypes active in her psyche, including the female artist, father and child.

Carl Jung states that, “Behind every individual father there stands the primordial image of the Father.” [8]

“Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son, Robert Kelso Cassatt,” Mary Cassatt, 1884. Picture via Wikipedia.com

The press release mentions a Mary Cassatt painting of a father and son. Comparing this to Stiler’s work, we can see that the latter has stripped away all of the impressionistic preoccupation with the intimate — pronouncing the archetypal core of such motifs.

Below, I provide a few short inquires regarding the themes of the archetypal father and child.

i. The Father and His Son

Firstly, In Jungian psychology, “The father archetype serves as regulator of boundaries, restrictions and social values that are imposed as rules and laws.” [9] However, it is important to understand that archetypes are patterns of behavior and indicate principles. Therefore the “father” (and “mother”) is active as a sub-personality within the psychology of all individuals, regardless of gender. It only becomes lacking when it is projected and therefore carried by another person. This can occur for both personal or cultural reasons.

So, aspects of the archetypal father, including “reflection, order, discipline, boundaries and skills” [10] will become active in a woman who takes responsibility for her child independently, or in conjunction with an egalitarian-minded partner.

It’s possible that Ruby Sky Stiler’s recent meditations on the father image refer to an activation, or shifting nuance of this archetype within her psyche.

“Abraham's Sacrifice,” Rembrandt, 1655. Picture via https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/373081

ii. The Son

Secondly, we can speak of the child as son. Throughout myths and religion, the unusual relationship between the father, son and transcendent deity is made clear. A fundamental story in Judaism, Christianity and Islam is the sacrifice Abraham is willing to make of his son for God.

There was no more significant sacrifice in the ancient, patriarchal world than the first-born son. This motif is an allegory for the evolutionary significant recognition in mankind that sacrificing one’s attachments, desires and impulses for the transcendent demands and rules is worthwhile and expected.

Increasingly, throughout the development of Western religion the symbol of the sacrifice of the son to the Heavenly Father, becomes more symbolic. Theologically speaking, Christ is the “last sacrifice.” But like the Son of God, each of us makes the sacrifice of our little self (son) to the larger self (Heavenly Father), when we sacrifice immediate pleasure for the goodness of our potential future. These commandments, rules and principles to live by are now ingrained expectations of existence, and modern people don’t often worship sacrifice or refer to ancient allegory. However, any able parent of a baby or young child will attest to their willingness to sacrifice the pleasures of life before children, not to mention a good night’s sleep, for a greater fulfillment.

iii. The Child

The shift in the personality that can be observed from the young adult to the parent is evidence of the possibility of the human personality to transform from and transcend beyond its previous states.

The archetype of the child is a symbol of this process and potentiality.

Carl Jung elucidates the theme best:

“Life is a flux, a flowing into the future, and not a stoppage or a backwash. It is therefore not surprising that so many of the mythological saviors are child gods. The “child” paves the way for a future change of personality. In the individuation process, it anticipates the figure that comes from the synthesis of conscious and unconscious elements in the personality.” [11]

The transcendent aspect of the child is sometimes emphasized in what Jung calls its “twice-born,” “dual descent,” or “double birth.” For example, Hercules had three parents, two mortal and one divine. Zeus, the father of Dionysus, got in a particularly gruesome love triangle when his wife Hera tore his love-child away from the mother’s womb. Dionysus gestated in his father’s thigh until birth. Finally, Christ is symbolically born twice: once by his mother, and a second time by the Holy Spirit, in his baptism with John.

This motif indicates that the pattern of transformation evident in the human personality, and implicates a transcendent potentiality that draws life forth, is symbolized by the child.

Conclusion

Each time Ruby Sky Stiler creates a new assemblage she births a new potentiality. In every instance that the artist balances her creative impulses, ambitious goals with her family life, she brings into harmony the archetypal feminine and masculine within herself. And with each show, she inspires audiences to reconcile their ideas of history and beauty, as well as what it means to live today as ever before.

Footnotes

1: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum: Ruby Sky Stiler: Ghost Versions, https://issuu.com/aldrichmuseum/docs/aldrichbrochure_stiler

2: For more read: “Byzantium set a standard for luxury, beauty, and learning that inspired the Latin West and the Islamic East.” https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/byza/hd_byza.htm

3: "The Survival of Magic Arts." In The Conflict Between Paganism and Christianity in the Fourth Century,” https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/popu/hd_popu.htm

4: Press release for “Father’s and Sons,” via https://nicellebeauchene.com/exhibitions/fathers/#bottom-copy

5: “Goddesses in Everywoman,” Jean Shinoda Bolen, Haper Books 1984. Chapter on “Aphrodite, The Alchemical Goddess: Creativity (emphasis my own)

6: “In Words: Ruby Sky Stiler,” Interview by Kelly Devine Thomas, 2009. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/in-words-ruby-sky-stiler/

7: Ibid (emphasis my own)

8: Carl Jung, Collected Works Volume 17, par. 97

9: Father Archetype,” Vladislav Solc, 2013. http://www.therapyvlado.com/english/father-archetype/ (emphasis my own)

10: Ibid (emphasis my own)

11: Carl Jung, Collected Works Volume 9, Part 1, par. 278