Part One

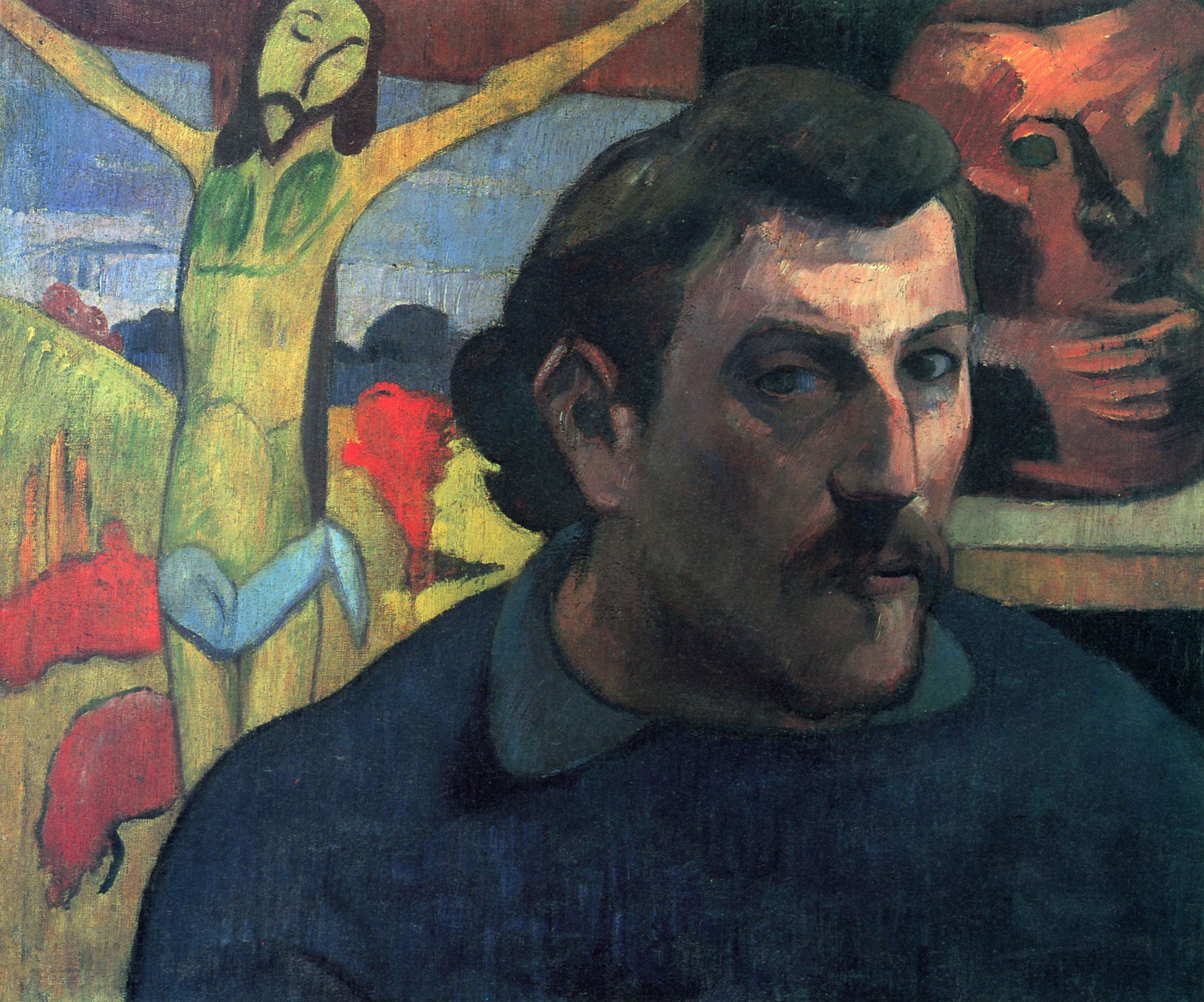

Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait with the Yellow Christ, 1890-1891

I. Introduction

Paul Gauguin, a painter of the 1890’s, achieved an immortality through his art. Much of his drive to create was a compulsion in which he sacrificed his well-being to achieve. Yet, the contents of his imagination and intellect live on in the cultural canon of Western art, and his aesthetics propagated a new vision of art, influencing the likes of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. The psychological power behind such a drive will be explored in this essay, along with much more.

Crucial to an interpretation of Gauguin is understanding the movement of artists known as the Symbolists. With Gauguin at the forefront, the group’s innovations coincided with the psychological discovery of the unconscious. As Gauguin created images from his dreams and unleashed a raw sexuality onto canvas, Sigmund Freud simultaneously was studying the images of European dreams and writing about repressed sexuality.

This essay will fastidiously analyze Gauguin, both as a historical figure, and as a subject to contain and crystallize psychological studies in the tradition of Carl Jung. We will focus on the male psychology of the artist, with Gauguin as the central example.

As with everything in reality, the myth of Gauguin is not pure; his heroic efforts had their dark side. Parsing through the self-mythologizing and historical record, we discover an extremely complicated man, spiritually, sexually and creatively, which leaves a wellspring of content to examine.

II. Loti and Tehamana: Erotic Controversy

What the average viewer will know about Paul Gauguin is that he painted “Tahitian Women.” And a typical article in the present day will deal with his infamous sexual encounters with underage girls.

Truly, part of the fantasy that lead Gauguin to Polynesia included unrestricted sex with exotic women. Critics and audiences have often fixated on this element of his story, which the artist exaggerated himself.

Gauguin’s ambition pushed him for original subjects. After early creative success, painting among contemporaries in a rural area of France, called Brittany, Gauguin sought a subject which could be entirely his own. He found this in a book by Pierre Loti titled, Tahiti: The Marriage Of Loti.

This French novel told the story of a young naval officer who marries a fourteen-year-old Polynesian. The French colony of Tahiti held a sensual mystique for the “civilized” Europeans. Loti’s novel provided a fantasy nourishment: “Yearning for an unspoiled Eden, the inhabitants of those overcrowded, smoky cities had no wish to be told such a paradise did not exist — least of all a fantasist like Paul Gauguin, who read Loti and through him came to see in the colonial romance a solution to his troubles, both financial and artistic.”[1] Loti’s borderline erotica depicted a vision of “Eden, before the fall, a world without sexual shame.” This would become central to Gauguin’s opus — an achievement tainted with the pedophilia and colonial attitudes that intertwined the artist with his broader cultural context.

The age of consent in Europe at the time was extremely young. But, love affairs between men and girls as young as thirteen would’ve been considered immoral. However, Westerners made exception for what was in distant lands and in the pages of literature.

It is easy to condemn Gauguin for the cultural values held almost two centuries ago. But, even today there are similar practices occurring in Islamic countries. If we assert today’s Western standard and denounce the marrying off of child brides in India or Yemen,[2] it doesn’t change the fact that it is perceived as acceptable there. This is the reality of historical and worldly affairs — they can be absurd and gruesome, but the people inside a certain time and place see no issue, and do not understand the psychological consequences of underage marriage, for example.

In Gauguin’s Intimate Journals[3] he repeatedly refers to the age thirteen as that of having come to womanhood. Even still, he was well aware that, being a man in his early forties, taking a mistress so much younger than him was provocative. It is historically likely that the “vahine” (young woman) that Gauguin took as a mistress was aged sixteen or seventeen. However, the notion of a thirteen year old bride, despite being a fabrication of the artist, has been widely reported as fact ever since his death.

Gauguin’s Manao Tupapau (Spirit of the Dead Watching) is a thinly veiled attempt to shock audiences back in Paris. Gauguin’s composition was a deliberate attempt to get attention from critics, propelled by his competitive drive and desperation for recognition. He knew that painting such a young girl would, under any circumstances, be perceived as indecent — and hopefully cause controversy.

“The girl in the painting is almost unique in his Tahitian works; most of his female figures are much older. The key to the work is surely his desire to out-shock Manet and Loti, a fact borne out of his subsequent attempts to play down what he had done, for, having made his challenge, he was immediately concerned that he might have gone too far.”[4]

We will examine more thoroughly Manet’s Olympia, a painting which was provocative and challenging in its own right. For now, it suffices to say that the fixation on the year thirteen and the moral violation (however fabricated) of Manao Tupapau will always taint Gauguin’s legacy.

Those who do parse through the facts manage to perpetuate the swollen importance of Gauguin’s painting: “Many can’t get past that creepiness, just as many can’t abide Wagner’s anti-Semitism, de Chirico’s Fascism, Roman Polanski’s sexual transgressions.”[5]

Gauguin’s fictionalized fixation on the age thirteen and the companioning painting which reads as a kind of proof, does not encapsulate the entirety his artistic endeavors. To understand the painter’s wider contributions, we will have to sort through his own psychology and cultural context.

In 2017, a show at the Chicago Institute for the Arts broadened the scope on Gauguin, and encourages viewers and academics to reorient the importance of Polynesia to Gauguin’s achievement:

“If you recoil, justifiably, at the colonial privilege and male dominance that underlie Gauguin’s late paintings — then I plead with you: See this show. By concentrating on the decorative arts, the monstrous vases and the whittled totems, the Art Institute’s show starts to map an approach to contemporary studies of Gauguin that goes beyond that balance-sheet rundown. It insists that what he made, why he made it and how he made it are all intertwined; that we must be formalists and feminists at once; and that we should all be a touch less sure of our responses.”

But let’s get real: Is it only the abuses and arrogations that make us bridle when we look at him, or is there something more? Can we accept that we might be scared of Gauguin’s utter freedom — a freedom almost none of us will ever taste ourselves?”[6]

These questions are what my essay will answer, as I prod deeper into the recesses of the European psyche, and the collective movements and individual developments which still remain intellectually and spiritually poignant for us all.

III. Development of the Psychology of the Muse

i. Origins of, and Extrapolations on the Sex Drive

Let us explore the sexual themes in Gaugin’s art more closely, beginning with the origins of the human sex drive. Darwinian theory states that the instinctual drive to propagate the genome is programmed into our biology. These biological instincts are the genetic underpinning of the archetypal symbols which manifest in the human psyche.[7] The relentless attraction towards a mate and the pleasure of sex are, at least partly, incentives towards the continuation of the species. This instinctive desire is psychologically, or symbolically, connected to the image of immortality, which has been expressed throughout all of human history.

Now we will further explore the archetype of immortality, as separate, yet connected to sexual desire. Procreation is the “passing down” of our genetic material, so that we can “live on.” The motif of immortality is perennial, and therefore archetypal.

In the West, the custom of passing on the surname of the father through the generations of sons is a way of immortalizing some part of themselves. In the dawn of humanity, an understanding of fidelity was limited; realizing the connection between insemination, pregnancy and paternal responsibility was a slow process. If a man identified a woman’s offspring as his own, it meant a physical investment (i.e. protection and hunting) in his genetic material. The psychological projection of genetic immortality developed a tradition of surname acquisition, which solidifies his commitment.

The drive toward immortality was further embodied by Pharaohs and elites in ancient Egypt who engaged in elaborate rituals, had their bodies mummified and were buried with all of their belongings, which they believed traveled with them into the afterlife. In some sense, a few of those individuals have become immortal. Tutankhamun’s spirit has far outlasted his corporeal existence: People travel to tour his possessions; television shows fantasize about his life and bring his personality into the present day.

In modern times, technology has taken on the role that spiritual ritual had in ancient times. Technology writer and futurist, Ray Kurzweil believes that his father’s consciousness can be immortalized with use of Artificial Intelligence.

As much as there is a sexual drive, there is also a drive towards consciousness — that is, the separation of the individual ego out of the unconscious.[8] Immortality can be understood as a projective conceptualization of the constancy of the ego throughout the challenges and transformations of an individual's’ life.[9] In other words, “You” “live on” despite minor or radical changes in your appearance, ideas and relationships.

Therefore the sexual procreation as genetic immortality can be separated from psychological immortality, the latter of which manifests in projection of an afterlife in heaven, the yogic master who lives on in the astral plane, or as the perfect Buddha who transcends death.

ii. Desire and Incarnation

Regardless of the goal, whether it be embracing life or attempting to transcend it, there is no doubt that living entails “doing,” and that nothing is done without desire.

In antiquity, Buddhist monks meditated on the corpses of beautiful women in order to extinguish sensual desires.

Arthur C. Brooks of the New York Times reports that, to this day, monk’s in Thailand meditate on photographs of corpses. This morbid practice “makes disciples aware of the transitory nature of their own physical lives and stimulates a realignment between momentary desires and existential goals.”[10]

In this example, we can see the attempt to separate and select conscious value-goals over impulsive desire.

Carl Jung studied ancient alchemy, understanding that it held a reservoir psychological symbols. On this topic he explained that:

“Sulphur represents the active substance of the sun or, in psychological language, the motive factor in consciousness: on the one hand the will, which can best be regarded as a dynamism subordinated to consciousness, and on the other hand compulsion, an involuntary motivation or impulse ranging from mere interest to possession in proper. The unconscious dynamism would correspond to sulphur, for compulsion is the great mystery of human life. It is the thwarting of our conscious will and of our reason by an inflammable element within us, appearing now as a consuming fire and now as a life-giving warmth.[11]

It is this desire, either from our will or as an impulse from the unconscious, that causes us to act. A primary biological desire would be the compulsion towards sex acts, while psychological desires may be multifaceted and unique. All the same, it is “desirousness — the striving for power and pleasure — that coagulates.”[12] This literally to say: as embodied beings, it is when we are acting in the world that we are truly alive.

The conflict between sexual desire and spiritual goals has been left unresolved and gone through many changes in human history. A general view of ancient religion will note that: In the East monks and yogis have attempted to renounce sexuality in order to achieve enlightenment; in the West, Christianity has condemned the flesh as sinful.

“Now the works of the flesh are manifest which are these: adultery, fornication, uncleanness, lasciviousness, idolatry…strife, seditions, heresies, envyings…drunkenness…” (Gal. 5:19-21, AV).

Desirousness is connected to the body, but also the image of incarnation. In The Tibetan Book of the Dead, “when a soul is about to be reincarnated and lodged in a womb, it has visions of mating couples and is overcome by intense desire.”[13]

The act of coming into the world, or being embodied, is arrived at through the mother — hence the association of the feminine with desire. Edinger explains in his chapter on coagulatio:

“Country, church, community, family, vocation, personal relationship — all enlist our commitment via the feminine principle. Even apparent abstractions such as science, wisdom, truth, beauty, liberty…when they are served in a concert and realistic way, are experienced as personifications of the feminine.”[14]

An artist strives and burns with passion for the pursuit of beauty. His source of inspiration is often the concrete woman, as “muse.” Examining this dynamic in man’s psyche will allow us to bring Gauguin back into focus.

iii. Summary: From Immortality to the Muse

Being that this essay is focused on the male psychology, as related to man as artist, and his muse, we use Gauguin as a subject. The authentic and prolific artist has a compulsion that drives him to create. He lives for the collective as much for his own sake (that we will return to later). His unconscious drive to create must be fed. The muse acts as a potent and charged energetic catalyst towards his actions. A beautiful woman stimulates the sexual response, which has as a backdrop the immense goal of immortality. Further, she may carry the projection of abstract ideas and notions, which wish to be carried through into existence. Through this interaction the artist is inspired and acts; he paints, sculpts, writes. Finally, and if recognized for an important contribution, the artist has immortalized himself through the creation of objects.

Gauguin is an important example of this process.

Footnotes:

1: David Sweetman, Paul Gauguin: A Life, pg. 151 (Simon & Schuster; First Edition, 1996)

2: Amit Anand Choudhary, Sex With Minor Wife is Considered to Be Rape Says Supreme Court of India, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/sex-with-minor-wife-is-to-be-considered-rape-says-supreme-court/articleshow/61032380.cms (2017)

3: Paul Gauguin, Gauguin's Intimate Journals (Dover Fine Art, History of Art, 2011)

4: David Sweetman, Paul Gauguin: A Life, pg. 328 (Simon & Schuster; First Edition, 1996)

5: Jason Farago, Gauguin: It’s Not Just Genius vs. Monster, New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/09/arts/design/gauguin-its-not-just-genius-vs-monster.html?_r=0 (2017)

6: Ibid

7: As Carl Jung writes in Carl Jung, CW Volume 9i, Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, Par. 91: “Moreover, the instincts are not vague and indefinite by nature, but are specifically formed motive forces which, long before there is any consciousness, and in spite of any degree of consciousness later on, pursue their inherent goals. Consequently they form very close analogies to the archetypes, so close, in fact, that there is good reason for supposing that the archetypes are the unconscious images of the instincts themselves, in other words, that they are patterns of instinctual behaviour.”

8: For more on this read: Carl Jung, The Secret of The Golden Flower

9: For more on this read: Erik Neumann, Origins and History of Consciousness

10: Arthur C. Brooks, To Be Happier Start Thinking More About Your Death, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/10/opinion/sunday/to-be-happier-start-thinking-more-about-your-death.html (2017)

11: Carl Jung, Mysterium Conjunctionis, CW 14, par. 141

12: Edward Edinger, Anatomy of Psyche: Alchemical Symbolism in Psychotherapy, pg. 87 (Open Court Publishing Company; 3rd Edition, 1991)

13: Ibid, cites: Evans-Wentz, ed. The Tibetan Book of the Dead, pp xiv. Ff.

14: Ibid, pg. 97